“I’ve got much more than most people have

And a little less than a few

But you can’t measure these things by weight

They either drag you down or they lift you.

“A Brand New Book,” 1991, Graham Parker

Late last year, I learned, to my delight, AARP magazine would be publishing an edited version of my Lifers essay sometime in 2018. The essay details the realization that, despite not having achieved youthful goals, playing music for fun is, in fact, a pleasure. And the irony that I’m better now than I was then. (Publication is imminent.)

In preparation, a few weeks ago, AARP sent photographer Gregg Segal to get shots of me on my home turf here in the Hudson Valley, playing music with friends in my backyard, performing solo acoustic at the humble Woodstock Farm Festival, and posing at the Colony, the venue I play most frequently these days.

AARP told me Gregg got some great stuff. It was, indeed, a fun, sunny day, ending with a lush Catskills summer twilight, and I was among good friends, hale and hearty family, in excellent health myself, doing well in the supportive and nurturing community I’ve called home for the last sixteen years.

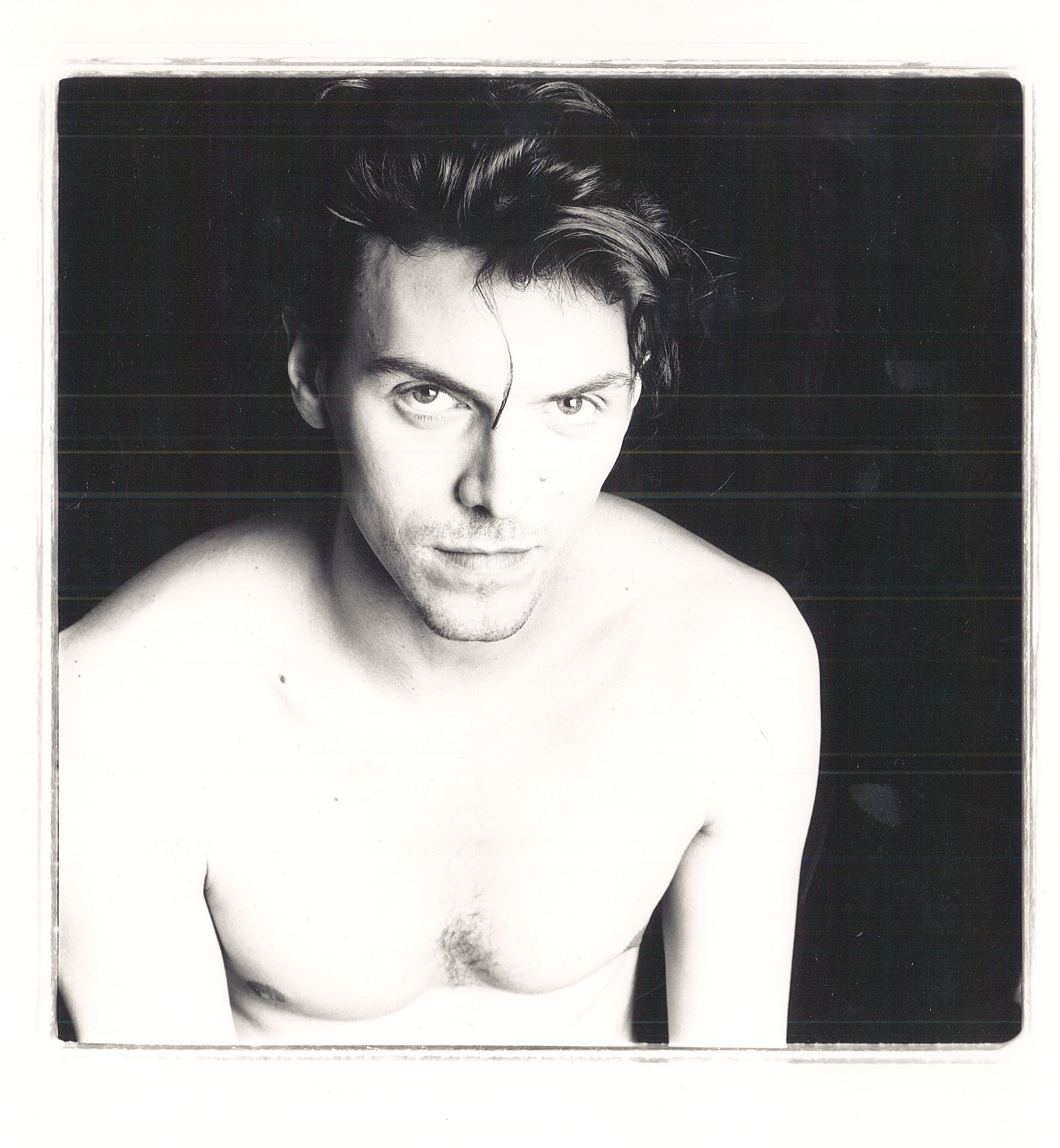

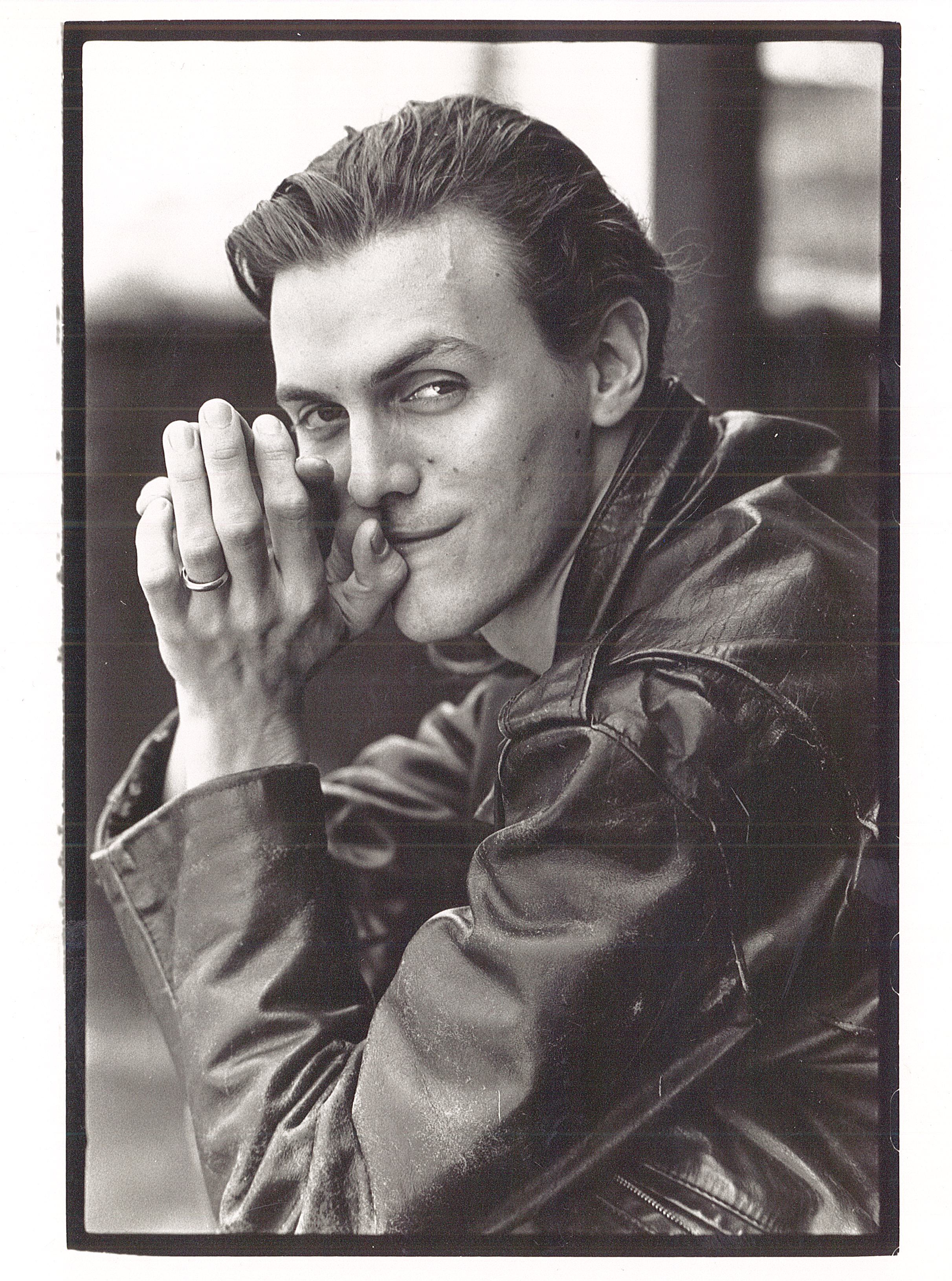

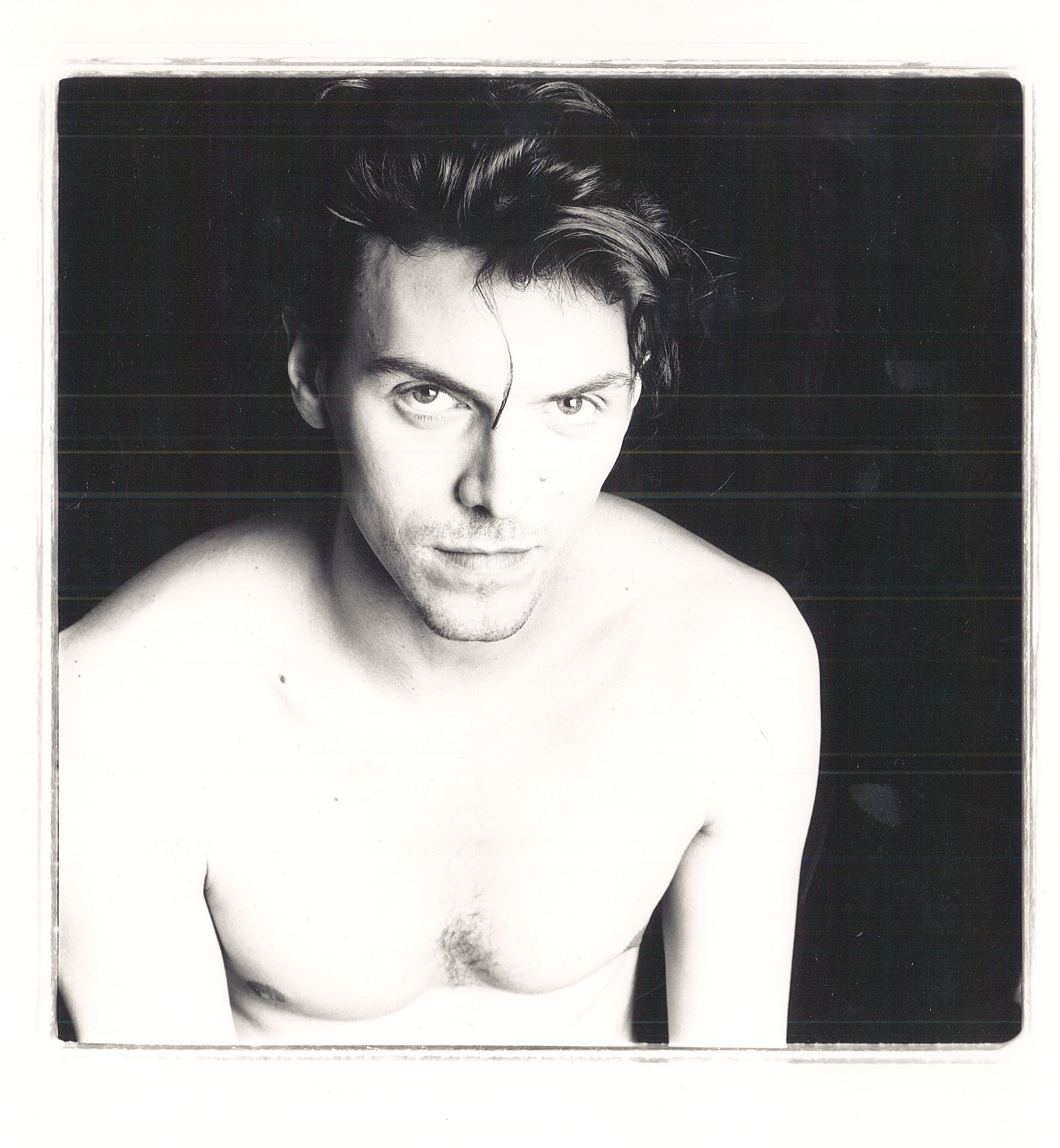

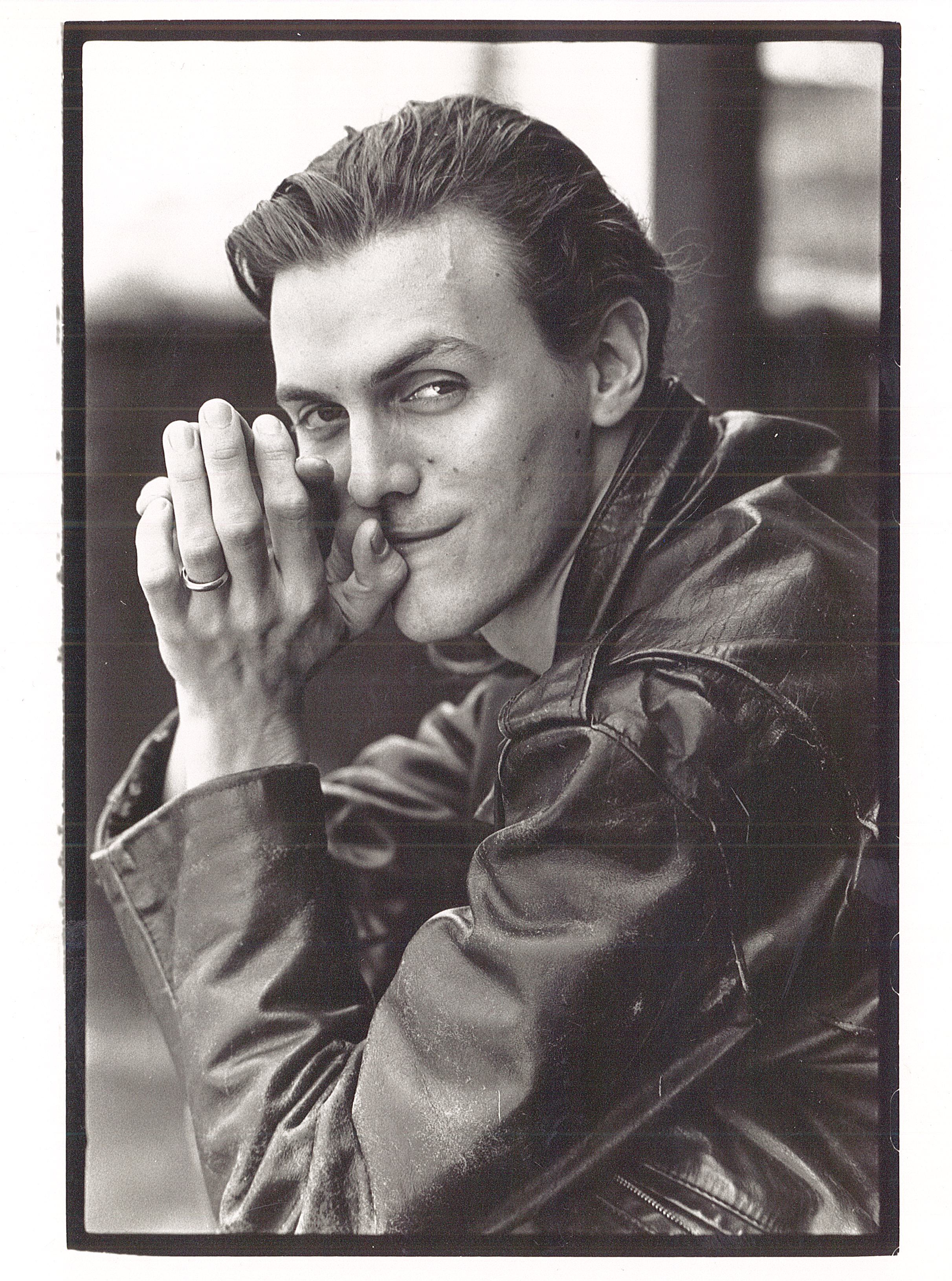

The AARP photo editor asked if I had any pix of myself from “back in the day” to juxtapose with Gregg’s shots. Turns out I do, both jpegs, and pre-digital prints I’d not looked at in years. These I needed to excavate and scan. This process brought me face to face with the work of two dear friends from “the old days”: photographers Dan Howell and Jimmy Cohrssen. Both of these men I am still in touch with via the internet, but I rarely see them, as the kids say, “in real life” (IRL). We were once significant parts of each others’ lives. In those days none of us owned laptops or cell phones, and were not yet thirty.

While I was pounding the NYC pavement in the 80s and 90s, Dan and Jimmy were setting out on their paths to become professional photographers. None of us, incidentally, had backup plans if our ambitions did not pan out. We were hungry dreamers. We encouraged and consoled each other, and we had some adventures and misadventures. To my great fortune, I was their frequent test subject, and they showed their belief in me by making many prints for nothing. Neither was a big drinker, so I couldn’t reciprocate with free booze at my various bartending gigs. They didn’t care.

Those times, those friendships, that heart-full emotion of knowing you are at the beginning of something – all neatly tucked away in my memory. Until, of course, I held the prints in my hands again.

I am happy to say I was mindful to store the Cohrssen and Howell prints – and a few others – quite well. That is telling. I have not been so good at storing other things well. But evidently, with these marvelous photos, I knew I possessed hard copy documents whose value would increase with time, at least in my house. If I’d allowed them to decay, I knew I would not forgive myself, and Dan and Jimmy would be understandably pissed. I had, in fact, already allowed some precious tapes, magazine clips, correspondence, and other photos to degrade in what I’d come to realize was subconscious destructiveness. For that I felt – and still feel – idiotic. With these prints, however, I’d vowed to be careful, to respect my friends’ work, to honor them and my erstwhile self.

I dimly recall painstakingly sealing the prints in a plastic tub well over a decade ago, storing them like a time capsule in a cedar drawer. All these actions were pre-digital, which, oddly, makes them feel like ancient history. But it was only the mid ‘aughts. I recall the strange, unstuck-in-time feeling of communing with the ghosts of my past and future selves, introducing two different versions of myself to each other, then stepping away from this disorienting headspace and back into the onward rush of my timeline, which in the early ‘aughts was pretty intense, if not quite glamorous. Certainly not boring.

On top of the tub was the New York Times from Wednesday, November 5th, 2008: OBAMA. Stored not quite so carefully, yellowed, not sealed in plastic. When I saw that, my gut tightened, and I knew I was heading into fraught territory, about to sail around a bend to rough waters, in which I would feel, with excruciating freshness, losses, both in my life and in my world. I was going to cry. And I did.

RBW, NYC, 1990, by Jimmy Cohrssen

RBW, NYC, 1991 by Dan Howell

RBW, NYC, 1993, by Alexa Garbarino

After pulling myself together, I looked at the photos and realized: the guy in these photos has had an interesting life up to the point of the photo, and yeah, he’s full of youthful vigor and trying to make the most of it, to document it with the help of his friends, and yeah, he’s vain, a little presumptuous. But I don’t begrudge him any of that. In part because he’s about to get his ass kicked, literally and figuratively, in both good and bad ways. He has yet so much life a-comin’, so much to be done and to deal with. He will, in fact, do his best work after these photos.

I realize with stunning clarity the life yet to be lived, the joy and despair, and every gradation of emotion in-between. The level of fame and monetary success he seeks will not be forthcoming, but in many respects he will be luckier than most, though it will take some effort and guidance to realize this.

As I look at the images, I make a by-no-means–comprehensive list of what is yet to come for this guy. It goes on and on and on, which in itself feels lucky, as I now have said farewell to quite a few whose lists ended years ago, long before they should have. People I mourn still. I realize if I do this again in twenty-five or so years, I will be in my late seventies. If I get that much time, what, I wonder, will I list? I cannot help but muse on that chronicle-to-be. For whom, if anyone, will it be a message? For you? Someone not yet born? Or just for me, a means of taking stock, realizing not only what I’ve done, but what I’ve survived? Not only what I’ve made, but what has made me.

Before I once again step away from this admittedly intense headspace and back into my timeline, I will farewell you with the current list, pasted below:

The guy in the pictures above has not yet

written a book

written a good story

written a good song

written an album

produced someone else’s album

written a decent essay / article, much less a great one

driven someone to tears with any of the above

attended a protest

co-produced a baby

seen a Sonogram

attended a birth, wishing he could do more, feeling like God had let him backstage, and leaving that room forever humbled

changed a diaper

cleaned up baby vomit (and other effluvium)

broken up a toddler fight

had a baby fall asleep on his chest/on his back/in the Bjorn

made children – and their parents – dance and sing together

wept with gratitude

taught a word

taught a dance

taught a class

taught a concept

been entrusted with two dozen toddlers

read a child to sleep

read an adult to sleep

nitpicked (lice, that is)

produced an event

hushed an audience with words and/or song, both his own, and others’

carried a 3 hour show

performed a great show without having slept in 36 hours, and without the aid of drugs

had what was once referred to as “a nervous breakdown” (and recovered)

walked away from a dream

watched friends achieve dreams like the one he walked away from

said goodbye to New York City

been amazed at how leaving NYC didn’t, in fact, send him into deep depression

held elected office (8th Grade doesn’t count)

spoken before elected officials

sung before elected officials

affected an election

published a poem

performed solo acoustic without subsequently breaking into tears of rage and humiliation

unpacked “issues” for a mental health professional

tried to work out said issues via art

taken prescription medicine

taken holistic medicine

communed with God (or…something) on an Andean mountaintop

learned songs written before 1956

heard his song on network TV

heard his song on satellite radio

received a royalty check

had a song plagiarized

had a root canal

met a murderer (Robert Blake)

attended the funeral of a friend

met an idol (John Paul Jones)

talked to – interviewed, actually – Stevie Nicks

played music in a children’s cancer ward, and been subsequently, radically changed

said goodbye to a brain dead friend in an ICU, and subsequently received notification that friend’s organs had saved three lives

received news that his dearest friend committed suicide

become a parent

watched friends become parents

watched friends become grandparents

watched friends get kicked to the curb by their kids

felt like a bad parent

flet like a good parent, then felt like a bad parent again

watched friends go through unspeakable grief

learned he is, according to a DNA test, 8% Native American, 92% European white guy

learned some devastating family history

been told he’s “too old to get testicular cancer” (uh… thanks?)

had a colonoscopy, with most awesome Propofol high

held the following live wild animals in his hands: robin, starling, hummingbird, bat, flying squirrel, mouse, chipmunk, snapping turtle

helped a crazed woman pull a dead black bear off the highway at night

come face to face with a very alive black bear in his backyard

seen a bald eagle mere feet away, and freaked out (in a good way)

heard coyotes laughing in his yard at night

made a deathbed promise

pierced the veil between the living and the dead

been in a room with a recently deceased person

voted for a winning presidential candidate

cut off an addict

forgiven an addict

attended a 12-step meeting

written epic, raging letters

been told he’s “a bit much”

negotiated a fee

been totally ripped off

been paid handsomely

had clothing tailor-made

done his taxes

signed a mortgage

signed a lease

sold himself short

been forgiven causing great pain

raged in public

set foot in a gym

set foot in a yoga studio

beat a traffic ticket

won, or rather settled, a lawsuit

lost, or rather settled, a lawsuit

spent more than $50 on a shirt

attended a protest

sent an email

wasted time on the internet

pulled someone from a riptide

been punched in the face on the street by a stranger (soon, though)

chopped and stacked wood

shoveled snow

kept a garden

made a pie

done battle with weeds

established a friendship with someone whose politics differ significantly from his own

cried in a theater

cried from a book

run across the street in the wee hours to tell the guys playing free jazz to fucking STOP already, as his pregnant wife can’t sleep

burned an heirloom Confederate flag

talked to the man who last saw his father alive

successfully performed downward facing dog (with feet flat) in a yoga class (that’s this month, btw)

made a list of life events for someone as yet unseen