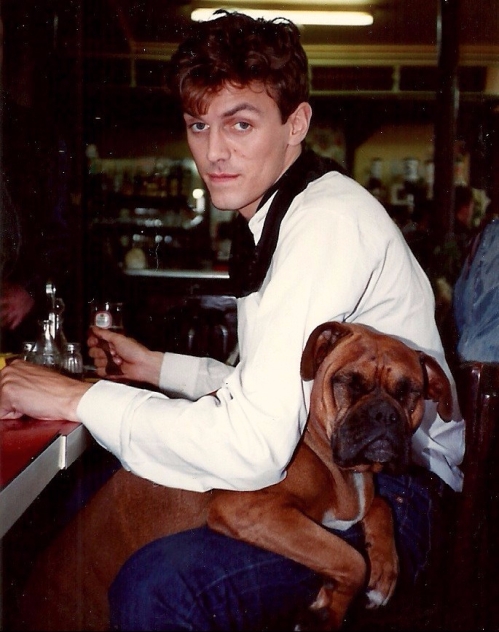

RBW, Paris, ’87

FLESHTONES MANAGER BOB SINGERMAN was on the phone. The band had discovered me playing bass for the drag queens at the second annual Wigstock Festival in Tompkins Square Park; Fleshtones’ guitarist Keith Streng later met me in King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut, where I tended bar; they’d lost their bass player, and was I interested in auditioning? I said hell yes, and the gig was now mine. A new album, Fleshtones vs. Reality, was about to drop, and tours were imminent. Bob was calling to give me details. It was late 1986. I was twenty-one.

“Robert,” Bob said, a smile in his voice, “how do feel about… opening for James Brown?”

From my rumpled sheets in a three-room tenement on Avenue B in the East Village, I told him I felt great about that.

“How do you feel about opening for James Brown… in Paris? In April?”

Naturally, these were all rhetorical questions. I was beyond excited, like I-won-Lotto excited. First of all, I would be seeing Paris for the first time, and I’d be traveling under optimum circumstances – as a rock and roll ambassador. Secondly, I’d be sharing a stage with the Godfather of Soul, fer chrissakes, a mountain of a man whose music inspired and influenced me. Also, although I was a New Yorker, I’d been raised in Georgia, where James Brown enjoyed folk hero status, not unlike, say, Ted Turner, MLK, and Gladys Knight. In Georgia, my people proudly claimed Mr. Dynamite as one of our own.

It got better. Bob went on to explain that the Fleshtones would be beginning the French leg of a European tour with a one nighter opening for James Brown not just anywhere, but at the 16,000-seat Bercy arena, a venue only slightly smaller than Madison Square Garden. Mr. Brown’s single “Living In America,” from Rocky IV, was a hit, and he was enjoying yet another resurgence in popularity, especially in Europe.

While somewhat “underground” at home, the Fleshtones were very popular overseas, particularly in France, where they’d recorded not one but two live albums – Speed Connection I and Speed Connection II – at Paris’ famed Gibus club. They’d regaled me with tales of their previous exploits among the diehard French fans, all of whom worshipped rock and roll and were skilled at having a good time.

“Fasten your seat belt,” the Fleshtones’ red headed saxophonist Gordon Spaeth told me, grinning maniacally. “Or don’t.”

I quit the bars and spent the winter of ’86-’87 hitting the U.S. college and club circuit with my new friends. The band had already been at it for almost a decade, releasing several LPs and singles, and they were quite a well oiled machine into which I fit pretty easily. It was sweaty, intense, fun work. Singer Peter Zaremba, it turned out, was not unlike James Brown, conducting and morphing the grooves we laid down while simultaneously enrapturing audiences. Onstage, we were untouchable, playing marathon sets of our own mix of garage, psychedelia, and R & B, referencing great soul like Stax Records, edgy proto punk like The Stooges, and gutbucket blues like Howlin’ Wolf.

Peter was still hosting The Cutting Edge on MTV, a once-a-week lo-fi program showcasing up-and-coming bands like the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Husker Du, Los Lobos, and R.E.M. The band had been label mates with R.E.M. and the Go-Go’s, and enjoyed a loyal fanbase of college kids, new wavers, and some punks, all of whom turned out en masse to our shows, regularly packing clubs and small theaters to dance and holler and hang out with us. We toured into the south, arriving in New Orleans for Mardi Gras, stopping off in Athens, where Peter Buck joined us onstage and got us drunk back at his new house. Several times, we tooled up and down the East Coast in a van, arriving back at our practice space, the infamous urine-soaked Music Building in Hell’s Kitchen (“Madonna used to live here!”) in the chilly, wee small hours, unloading our gear with the help of our driver/road manager/sound man, and going home to sleep for a few days before heading out again, back into the buzz of the oncoming spring of ’87.

I was enjoying my first real taste of Life on the Road, watching the landscape zip by from a van window, often the only Fleshtone awake on the post-gig ride, my long legs cramped, ears ringing as my bandmates snored around me, their exhalations filling the Econoline with stale beer breath and various other man smells.

The guys took a real shine to me. They were all contentious and egotistical by nature – which is what you want in a rock band – and they nursed grudges at the world, insisting they should, in fact, be as famous as their ever-more-successful and inferior contemporaries. But for the hex someone had put on them, they would be. One of the Fleshtones’ best songs was actually called “Hexbreaker,” a funky rave up we usually saved for the end of the set. Several times, Zaremba looked at me in the darkness of the van, placed his big hands on my shoulders, and said: “You! You are the hexbreaker, Warren! You’re the hexbreaker! Our luck is gonna change!”

It was one of the happiest times of my life. And it was all prep for Paris.

The April afternoon we left JFK for Paris was a Perfect Manhattan Spring Day, blossoms in the East Village trees, bare-legged folks in T-shirts, music spilling onto the cracked pavement from open windows. Artists everywhere, all of us poor and, for the most part, happy; tolerated or even beamed at by the old Ukranians and Poles whose neighborhood we’d invaded.

Our meeting spot was outside the Pyramid Club on Avenue A. We waited for the van, our instruments and bags encircling us. Sweet anticipation connected all as we sat in the warm late afternoon sun. We laughed a lot. The van was running late, so I walked across the street to King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut to see some friends and have my customary double espresso with Sambuca. I must’ve been radiating something, because a beautiful young woman sidled up to me and struck up a conversation. I told her I was a bass player, and I was waiting for a van to take me to the airport, as my band was going on tour, and our first gig on French soil was opening for James Brown. I asked about her, and she told me, quite unapologetically, that she was a mistress. That was her job. And did I have time to come back to her apartment and, you know, hang out? I told her I did not. Sadly. She kissed me and told me to have a good time and be careful. I would never see her again.

About eighteen hours later, an official was stamping my passport at Charles de Gaulle airport. I rarely sleep on planes, and this flight had been no exception. I was too excited and amped up on coffee. These were the days when you could still smoke on planes, and even though I was not a smoker, I bummed a French cigarette – a Gauloise blonde – from a Parisian guy heading home. Just to have something to do, and to talk to a French person, as prep. He had not heard of my band, but was a fan of James Brown. Although Zaremba had told me I didn’t need to worry about speaking French, as I would be conversing in the language of rock and roll (this would turn out largely to be true) I still wanted to try to resurrect my high school French.

Friends of the band picked us up at the airport and, as French folk are wont to do, they took us to their house, where we sat, bleary-eyed behind our shades, on a terrace in a neighborhood on the outskirts of the city, and drank yet more (sublime) coffee, the best red wine I’d ever tasted, and Kronenbourg beer. I cracked open my first still-warm-from-the-neighborhood-bakery baguette and smeared it with the best butter I’d ever tasted. I caught the occasional word and gist of the conversations around me (although our hosts, like most French, endeavored most often to speak English in our company), and the name James Brown was excitedly uttered amid the occasional flurry of French. As the sun crept low over the russet tiles of the surrounding roofs, fatigue finally began to pull me under.

Another drive took us to our accommodations, the Hotel Regyns, in Montmartre. We careened down cobbled, tiny avenues, and diesel-choked thoroughfares, all of which looked, to my bloodshot eyes, like a cross between Breathless and the 1981 film Diva. Everyone was slim and urbane and beautiful, or dignified and happily elder, with, I shit you not, berets and tiny glasses of wine on folding tables outside apartments and cafes. Seemed like everyone was smoking, everywhere, and everyone was kissing hello. A subculture of dogs seemed to roam freely, even in and out of shops. And among the clearly Gauloise faces were enfolded Turks, Africans, Middle Easterners, every color of the world, gracefully woven into a fabric I could reach out and touch with my naked eyes and eager hands. It was even more effortlessly multi-culti than New York.

I felt like Henry Miller, like Jim Morrison, like I’d stepped into a painting, like I was falling, happily exhausted, into the embrace of an ancient culture of arts love, of sensual, guiltless pleasure. It began to dawn on me in a visceral sense that I was in the land where the creators are revered; Paris greets artists with an affection so strong it gives an energy boost, life force, enabling one to go back to the blank space with faith, with no fear. And indeed, I was not afraid. I was the opposite of afraid. They don’t call it the City of Lights just because it literally shines at night; they call it that because of what it does to your insides.

~

The tiny Hotel Regyns, overlooking the Place des Abbesses metro, was the rock and roll hotel of Paris, famed among bands as being laissez faire about all night carousing and guests. But none of us partied that night. In twenty-four hours, we would be rocking the Bercy. Best to be somewhat rested. We all crashed at a “reasonable hour” for once, our casement windows open to the misty springtime air laced with the scents of diesel and cooling stone.

I awoke around 4 AM, eyes wide, senses on hyper-alert. I got dressed, pulled on my Chelsea boots, and made my way through the streets of Montmartre as dawn paled the sky peach and the warm yeasty smell of bread baking rose in the coolness. I actually saw a squat, beret-wearing man in rumpled tweed walking along with a baguette tucked under his arm. I am in a tourist postcard, I thought. I found his bakery, a sunny little storefront where they smiled indulgently at my lousy French; I purchased coffee and the absolute finest croissants of my life, which I ate on the steps of Sacre Couer as the sun lit the red ceramic roof tiles of the 18th arrondissement. I made my way back to the hotel, passing the painters setting up their easels in the plaza, awaiting tourists; meanwhile, young, beautiful drunk couples were making their way back from nearby Pigalle to collapse in bed together. I bid them all a shy Bonjour and crawled back into my bed.

We arrived for sound check to the echoing strains of James Brown’s band laying into a hard groove: “(Get Up I Feel Like Being A) Sex Machine.” I heard James’ voice and hurried into the empty, cavernous house, where techs were rigging lighting and tweaking the massive sound system. I was stunned by the size. I’d never played anywhere remotely that large. Somewhat to my disappointment, James was not there. One of his backup singers, a slender man with a Jheri curl, was checking for him, sounding exactly like him.

The rest of the Fleshtones headed for our dressing room while I watched the bass player and sax great Maceo Parker navigate a couple more grooves. I finally approached and introduced myself, and they were nice as could be. The bassist had been in K.C. & the Sunshine Band, and that man was funky. Maceo, of course, was one of James Brown’s many indispensible collaborators, and clearly the actual bandleader. We chatted for a while and he said he’d try to get us an audience with James, the prospect of which made me ambivalent.

A few hours later, as we waited to go on, we were informed James couldn’t meet with us due to problems with his teeth. Maceo, however, came by to tell us to break a leg. We hit the stage and a cheer rose in the three-quarter filled venue, but the audience was not there for us. We rarely opened shows, and while our thirty minutes was fun indeed, it wasn’t nearly as fun as our usual club show, for which we were deservedly famous.

While most expressed appreciation to the five white dudes called the Fleshtones opening for the African-American dude who sings “I’m Black and I’m Proud,” at least one Parisian did not care for us. As I walked the lip of the stage during my fuzz bass solo, an orange object spun to my left. When the lights went up, I saw what it was: an orange-handled, blunt, rusted straight razor, flung at us during our set.

I showed it to Maceo who laughed like Santa Claus and went out and worked the Bercy crowd for about fifteen minutes, the band pumping behind him. He actually gave a more inspired, energetic performance than The Hardest Working Man in Show Business. Once James hit the stage, the energy level actually dropped. Nevertheless, it was an amazing show. An off day for James Brown is probably way better than a stellar day for most musicians.

When it was all over, we went to the Bataclan, danced and drank, then back through the lamplit streets to our hotel. We caught a few hours sleep, some of us alone, some of us not, before meeting our French road crew – two lovable, hardboiled Parisiens – who would drive us through Europe in a red converted bread truck, leaving a plume of diesel in our wake, listening to the Stooges on a handheld tape recorder.

Paris faded in the rearview, but we would soon return triumphantly after playing for adoring crowds in the provinces. At our final gig for this leg of the Fleshtones vs. Reality tour, before heading to Italy and Germany, we led the audience of La Locomotiv out of the club to the sidewalk, and we climbed into the trees, up among the streetlamps, our instruments dangling, completely unconcerned with possible trouble from the Gendarmes, because indeed, they did not care.

In time I would return again and again, as a Fleshtone, as a newlywed, and several more times as a visitor. I sought out the sad-eyed smiles of the citizens of the City of Lights; all speaking passionately of politics, art, and wine, no matter their standing: millionaire’s daughter or a squat dwelling punk. The welcome was always there, that familiar touch of the emboldening friend. That contagious passion drew me back again and again to my Paris, rock and roll town extraordinaire, multi-hued haven of beauty, art, erotica, and courage, all offered to anyone visiting the City on the Seine. I took all of it with me and ran into the creeping evening of age. But I will be back.

This essay originally appeared in The Weeklings